After returning to Poland the young violinist and composer faced new responsibilities. The man instrumental in this was Grzegorz Fitelberg, who “suggested” to Szymanowski that the piano score of the ballet Harnasiehe was waiting for should be prepared by Grażyna Bacewicz. He needed the score for the rehearsals of planned performances of the ballet in Prague and Paris. Drawing on Fitelberg’s advice, Bacewicz’s transcribed Szymanowski’s score for two pianos. In 1935 the transcription was published in Paris by Max Eschig.

In the 1933/1934 school year Grażyna Bacewicz began to work as a teacher at her alma mater in Łódź. She was entrusted with the teaching of the violin as well as harmony and counterpoint.

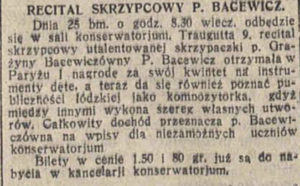

- Grażyna Bacewicz’s announcement in “Ilustrowana Republika” (1933)

- Press announcement of Grażyna Bacewicz’s recital at the Łódź Conservatory (Ilustrowana Republika, 1933)

At the same time she did not give up the concert invitations that continued to be extended to her from the Lithuanian circles, still favourably disposed towards her. She took part in chamber concerts, this time playing with Kiejstut, at that time a teacher at the State Gymnasium in Kaunas, and in symphonic concerts. She was the soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto; the Lithuanian audience also had an opportunity to get to know her Caricatures, performed in January 1934 in Vilnius under Vytautas’ baton. Her very favourable reviews must have reached Warsaw. Two years after her less than stellar grade at the final composition exam, on 10 May 1934 the Warsaw Conservatory organised a concert of Grażyna’s works. The programme featured two Capriccios for violin and piano, The Stained-Glass Widow, Andanteand Allegrofor violin and piano, several pieces for piano: Sonatina, Children’s Suiteand Scherzo, as well as two pieces in which Grażyna drew on the Lithuanian folklore: Theme with Variationsand Lithuanian Songfor violin and piano. The composer-cum-violinist was accompanied by Jerzy Lefeld on the piano. The programme also featured her Parisian award-winning Wind Quintet.All the proceeds from the concert were given by Bacewicz to the Bratnia Pomoc (Fraternal Help) aid organisation.

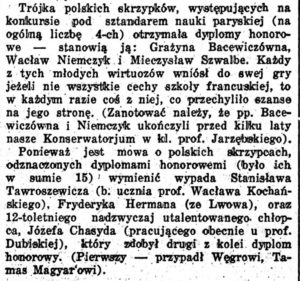

- Press note about the concert of Bacewicz’s works (Kurier Poznański, 1934)

The concert was noted by the newspaper Kurier Porannyand was also remembered by Grażyna’s younger colleague, Witold Lutosławski. In the 15 April 1969 issue of Ruch Muzyczny, published after the composer’s death, he wrote,

When I was a student, Grażyna gave her first recital as a composer at the Warsaw Conservatory. I remembered that evening very vividly, also because of the fact that as a pupil of Jerzy Lefeld I was his page turner as he accompanied Grażyna. She played her Capricci for violin, compositions far ahead in their significance of the traditional meaning of this virtuoso form. […] During the same concert Grażyna also played her piano pieces. These were faultless, excellent performances. From her very first independent steps one could see she was a natural-born, true musician, combining – like the great masters of the Baroque – the talent of a creator and a performer into one harmonious whole. Unfortunately, I did not have many opportunities to make music with Grażyna, but those few concerts during which I accompanied her, as part of Ormuz’s popularising activities, are etched in my memory as exceptional artistic experiences. Only while playing with soloists with unique, not learned but innate, wisdom, does the accompanist feel incomparably free and assured. Each interpretative nuance of the soloist seems obvious and any problems with playing together are solved within seconds. Grażyna probably brought this musical wisdom of hers to this world when she was born.

The harmony between the “talent of a creator and a performer”, as Witold Lutosławski beautifully wrote about his older colleague, prompted Bacewicz to take up another challenge. The year 1935 was announced as being the year of the 1st International Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition. The man who sought to organise such a competition was the great violinist’s nephew, Adam Wieniawski. He wanted to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his uncle’s birthday, popularise his oeuvre, but also provide young virtuosos with an opportunity to launch their concert careers. Grażyna Bacewicz decided to take part in the competition. To improve her technique, in 1934 she again went to Paris, where the eminent violinist and teacher Carl Flesch was staying for a few months.

But she did not forget about composing and began working on her Triofor oboe, violin and cello. Full of hope, in early 1935 she returned to Warsaw. She did not know that life would bring her many surprises – success as well as failures. She resumed her concert activities, from time to time also leading a string quartet, with Bogdan Łosakiewicz as the second violin. It was Łosakiewicz who one day brought his roommate to a concert. The roommate was Andrzej Biernacki, a great music lover and amateur pianist. This first meeting determined the future of the 26-year-old violinist and the 32-year-old physician. The two fell passionately in love and quickly decided to marry. But they both thought rationally about their lives and did not want to give up their earlier plans. Grażyna had her competition to think about, while Andrzej, thanks to a scholarship, was about to go on an internship in several European cities. The violinist recalled her participation in the competition in one of the stories from the Znak szczególny (A Distinguishing Mark) collection, entitled Pech (Bad Luck):

I prepared myself well – with Flesch. I worked with him for six months. He worked me very hard and sometimes even got angry at me, but wished me luck at the end (I wish I had touched wood then).

Grażyna Bacewicz, Znak szczególny, Warsaw, 1974.

Grażyna did very well in the first stage, the press got interested and there were predictions she would win a prize. The second stage was far worse. The young violinist disappointed. She received only a distinction and… a bouquet of flowers from Andrzej. The competition was won by the young Ginette Neveu (who later died in a plane crash), with David Oistrakh receiving the second prize. It was not until many years later that the composer explained the whole situation in the story Pech.One day before her appearance she listened to competition performances with her mother and sister. When the ladies returned home, it turned out that their flat had been burgled. A night at a police station caused her form to deteriorate. Grażyna was silent about this for many years. Perhaps it was an act of providence bringing her closer to the decision to abandon the violin in favour of composition? Because this is what happened – though not immediately.

- Grażyna Bacewicz (sitting first from the right) at President Mościcki’s party after the end of the Wieniawski Competition (NAC)

- Fragment of a press review of the Wieniawski Competition (Kurier Warszawski, 1935)

As early as in May that year Bacewicz resumed her concert activities. She completed her Triofor oboe, violin and cello. The piece won the second prize at a competition organised by the Polish Music Publishing Society in 1936. The first prize was not awarded, while the third went to the Triofor violin, viola and cello written by Marian Neuteich – a composer, cellist and conductor, founder of the Warsaw String Quartet. Neuteich’s subsequent fate was tragic – like many of his fellow Jews he perished during the Nazi occupation. Both award-winning Trios were performed at a concert at the Warsaw Conservatory attended by no less a figure than Sergei Prokofiev.

Here is an excerpt from a review by Michał Kondracki from 7 March 1936, published in Nowiny Codzienne:

The Polish Music Publishing Society organised a concert at the Conservatory, third this season, of contemporary chamber music, attended by the eminent Russian composer and pianist Sergei Prokofiev, who was visiting Warsaw. The programme of the concert featured some interesting novelties: two Trios which had won prizes at the Society’s competition, written by Polish composers, Grażyna Bacewicz and Marjan Neuteich, as well as a number of contemporary chamber compositions. The best piece performed at the concert (which sounds paradoxical!) was a trio for oboe, violin and cello by the young Grażyna Bacewicz performed by Śmiechowski [in fact, Śnieckowski – ed.], Kmitowa and Kalber. It is not that this very promising and talented composer is apparently equal in terms of power of her inspiration or value of her creations to Hindemith or Prokofiev. But she does have a lot of interesting ideas, freshness of invention (especially in the first and remarkable cantilena) and endearing sincerity in the way she expresses herself. One has the impression that composing is for her some inner need, necessity even and her element. May she develop successfully, may she grow, think a lot and critically, work and analyse, in a word – not to disappoint the hopes one may have for her after hearing the beautiful Adagio–Allegro and Vivace from her Trio.

Michał Kondracki, “Sergiusz Prokofjew na koncercie współczesnej muzyki”, Nowiny Codzienne 1936 no. 69, p. 4.

- Michał Kondracki’s review of the contemporary chamber music concert (Nowiny Codzienne, 1936)

At the Society’s competition for composers, on 15 March 1936, Bacewicz was awarded with a distinction for another Sinfoniettafor string orchestra (the manuscript bears the title of Simfonietta). The awards were a consolation for months of separation with her fiancé. Grażyna and Andrzej wrote each other letters, which in addition to totally private information also contained observations concerning the world around them and the clouds gathering over Europe. Grażyna even confided her creative dilemmas, revealing a bit of her personality. Her thoughts about both of her award-winning pieces are quite interesting. It turns out that the ideas of a composer do not always correspond to common views. Here is a mysterious letters sent after the premiere of the Sinfonietta in March 1936:

I had a very beautiful day yesterday. The Sinfonietta (not little Sinfonietta, as you write disparagingly, for which you’ll get such a trashing that you won’t be able to get up for a week), the Sinfonietta proved to be excellent. You know that I don’t like to boast and that I’m very critical about myself, but in this case there’s simply nothing I can find fault with. While the Trioseemed very good after I finished it and after its premiere I thought so only about the third movement, this piece seemed to be not quite right after I completed it and perfect after the premiere. You know, I really listened to it as if it weren’t mine, as if it had been written by some very wise composer. I can’t believe I have written it. It’s very lively, joyful, witty, not a second of long-windedness. I don’t quite understand how such a pessimistic creature like myself can write such joyful music. Ficio* liked it a lot, full of superlatives, those who listened to it – liked it too. My colleagues did their best.

Grażyna’s letter to Andrzej, in Joanna Sendłak, Z ogniem, Warsaw 2018, pp. 409—410. *Ficio — a diminutive of the name Fitelberg, used by Grzegorz Fitelberg’s friends.

The letters, hidden by Grażyna’s sister Wanda, were discovered after her death by Grażyna’s granddaughter Joanna Sendłak. Drawing on these documents, she wrote a quasi-biographical novel about the love of Grażyna and Andrzej entitled Z ogniem (With Fire) (Warsaw 2018).

Energy did not leave the young artist, who was a regular beaver. Her willingness to take on various tasks had been noticed by Grzegorz Fitelberg much earlier. As soon as he was entrusted with the Polish Radio Orchestra in October 1935, he invited Grażyna to join the ensemble. She accepted the invitation and sat in the first violin section. She was a bit perverse in doing that, as she wanted to become more familiar with the complicated orchestral apparatus in order to be able to compose for orchestra without any worries. Despite the fact that she often complained about the “despotism” of her boss, e.g. because of problems with getting a leave, she took active part in rehearsals and concerts, and the collaboration culminated with the premiere of Violin ConcertoNo. 1, which she composed in 1937. The premiere took place in March 1938, and the composer, who appeared as the soloist, was accompanied by “her” Polish Radio Orchestra conducted by Grzegorz Fitelberg.

- Grażyna Bacewicz in the Polish Radio Orchestra during a rehearsal, 1936, phot. Antoni Sitkowski (NAC)

Before that, in October 1936, the audience had an opportunity to hear a song of hers entitled “Mów do mnie, o miły” (Speak to me, my love) to words by Rabindranath Tagore translated by Jan Kasprowicz. The singer was Stanisława Korwin-Szymanowska, who was accompanied on the piano by Kiejstut Bacewicz. The piece is one of 12 songs composed by Bacewicz, as vocal music was definitely marginal in her work. What is significant is the title of the song, undoubtedly associated with her marriage. On 6 August 1936 Grażyna Bacewicz married Andrzej Biernacki, who had returned from his overseas travels. The newlyweds moved into a rented flat at ulica Koszykowa 35, where Grażyna would spend the next 26 years of her life.

She continued to compose. After the Violin Concertothe turn came for a symphony, which, however, the composer decided to eliminate. Dissatisfied with her work, Grażyna wrote more songs, this time to 10th-century Arabic poetry translated by Leopold Staff; in addition, after a break of seven years she returned to the form of string quartet. It was only this piece from 1938, in which she used Lithuanian folk music motifs for the last time, that she regarded as her first official quartet.

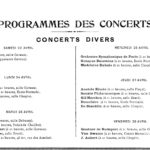

In early 1939 he went to Paris for the third time to take part is a concert featuring her compositions at the École Normale de Musique. In addition to the new Quartet, the programme also included Triofor oboe, violin and cello, Sonatafor piano, Theme with Variations, Lithuanian Song, Partitafor violin and piano, Children’s Suite, Scherzofor piano, andSonatafor oboe and piano. They were performed by artists like the Prof Bleuzet and Figeroa Quartet. Bacewicz’s stay in the French capital lasted until the summer of 1939. Soon after that Grażyna returned to Poland.

- Concert schedule in Paris in April 1939 (Le Temps, 1939)

- Concert schedule in Paris in April 1939 (Le Menestrel, 15 April 1939)

- Press note about Bacewicz’s successes in France, 1939 (PWM)