Composed in 1958, Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion became famous as a unique piece in the composer’s hitherto classicistic-folkloristic oeuvre. The sonoristic technique, manifestations of which can be found in the composer’s many earlier pieces, became here the main force driving the development of each of the three movements. The piece, having the same date as Witold Lutosławski’s Funeral Music, brings to mind another work as well – Béla Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. The affinity with the brilliant Hungarian’s work can be found in the main idea: distinguishing three concertante groups in the orchestra and among them individual instruments, and in some technical analogies, like motivic development from an embryonic cell, limited polyphony and sometimes parallel voices. Leon Markiewicz [“O niektórych cechach Muzyki na smyczki, trąbki i perkusję Grażyny Bacewicz”, Poznań 1998] points to a similarity to the chords used by Bartók, but leaves open the question of whether this was intentional or accidental. However, the analogies end on the technical, elementary level, for it is difficult to compare the language of the two pieces, their dramaturgy and their expression.

Grażyna Bacewicz’s Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion seems to be an apotheosis of pure power, an embodiment of the Nietzschean ideal of ruthless vitality and resilience of life. Although the piece was undoubtedly intended as an abstract work, its sound content encourages us to ascribe some meaning to it. The “Dionysian” vitality of movement I (Allegro), transfixing in its will to rush and reflected in the pensive mirror of movement II (Adagio), gives way at the end to the bright, joyful, “Apollonian” liveliness of movement III (Vivace).

Despite the novelty of its sound language, the piece does not lack some (neo)classical reminiscences, especially when it comes to its formal structure. The first movement, with its plan of a sonata allegro, is a structure based on two exposition themes, the first of which provides a characteristic expression to the whole movement. However, neither theme is a closed melodic idea, although the second theme contains a sophisticated canon in an inversion (violins and cellos), with a delay of a quaver, preserving the direction of the melody but not respecting strict interval sizes. After all, the development of the form is determined by the dynamism of movement, alternation of textures and variety of sound forms. The movement vector, constantly pointing forward, does make it possible, however, to develop some ideas in a broad sound space.

Theme I begins after an energetic introduction with a relentless monotony of a string tremolo, in some way drawing on the idea of the “pendular movement” from the Concerto for String Orchestra. Pendular figures, from which an accented note sometimes “leaps out” – by a augmented interval – are arranged alternatingly and asymmetrically, which creates an impression of meticulously planned “entropy” of the system, an impression enhanced by unevenly placed pizzicatos. This rushing stream grows steadily, encompassing an increasingly large interval range, only to turn – after a signal intervention of the trumpets and tremolo of the timpani – into a raucous, “turpist” tumult ending with a twelve-note aggregate.

After a moment of calm the trumpets enter with a quasi-theme, whose marching, broken rhythm, syncopated by double bass pizzicatos, resembles the mood of some fragments of Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale. The dreamy theme II, presented by the strings treated as solo instruments and counterpointed by the celesta, turns into the above mentioned canon, followed by a virtuoso transformation and then a mirror reprise.

The second movement is initially concertante music of solo instruments or their groups selected from the entire ensemble and shaping their elegiac phrase against a background of an almost “stationary” motif of two semiquavers and a quaver with a rotationally changed first note. The “epic” part and figurative transition, resembling old, progressively changing figures with a constant base in the form of the initial note, are followed by a mysterious “murmuring” fragment based on trills played by serially entering strings – from cellos (con sordino, ppp) to divided violins (con sordino, sul tasto, pp), as a result of which the composer achieves the effect of “diagonal” movement across the sound space. The fragment – complemented by a delicate tremolo of the snare drum and the timpani, delicate strokes of the celesta and trails of the trumpets – is an example of the composer’s unique impressionism, in which the play of motifs and rhythms is largely replaced by a play of colours, sound planes and textures.

The third movement is a veritable kaleidoscope of ideas, of events following one another, if threads from the past (ostinatos, pendular figures, parallel runs) as well as those that are completely new. They include the appearance of another “protagonist” – the xylophone. However, there is some order in the ideas, combining the concertante form with a form that has features of a sonata rondo.

Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion is dedicated to Jan Krenz. Under his baton the Polish Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra performed the work for the first time on 14 September 1959 at the Warsaw Autumn International Festival of Contemporary Music. In 1960 the piece was ranked third (the highest score among orchestral pieces) at the International Rostrum of Composers in Paris.

There have been many choreographic versions of the work. They include Quadrige by Pierre du Villard (1965), Witness of Innocence by David Earle (1967) and Three Pieces by Hans van Manen, prepared in 1968 for the Nederlands Dans Theater and revived since by other companies. In 1988 van Manen’s choreography was also presented at Warsaw’s Teatr Wielki by the Polish company. As we can read in the production’s programme booklet,

Three Pieces is an abstract work in three parts for eleven dancers, two pairs of soloists and one male soloist. With its contrasting counter currents of slow and rapid sequences, the ballet is a kind of dialogue (with a slightly erotic touch) between the choreography and our composer’s energetic, vigorous music.

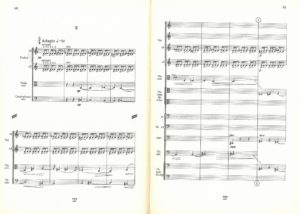

- Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion, PWM score, mov. 1

- Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion, PWM score, mov. 2

- Music for Strings, Trumpets and Percussion, PWM score, mov. 3