Grażyna Bacewicz was in Warsaw, when the war broke out. After the first bombardments in 1939, she and her family decided to leave the city. After reaching Garwolin she, guided by an inexplicable instinct, forced her loved ones to continue their journey. Looking back, the refugees saw the town being bombed [Grażyna describes this in the story Na naszych oczach(Before our eyes) from the collection Znak szczególny(A Distinguishing Mark), Warsaw 1964, pp. 59–61]. After a while the composer and her family returned to Warsaw. There Grażyna remained in regular touch with colleagues who had created an informal – not registered because of security reasons – Secret Association of Musicians. Its members included Piotr Perkowski, Edmund Rudnicki — Music Director of the Polish Radio – Bronisław Rutkowski, Tadeusz Ochlewski, Stefan Śledziński and other persons actively supporting the work of the association. Representatives of the Association were in constant touch with the London Government Delegation for Poland and the Main Welfare Council, as a result of which they were able to obtain funds to help musicians who could not earn their living. The Association also prepared concert programmes as well as projects to be implemented in the future after the war, which, the belief was, would end quickly. As we know from numerous descriptions, the German occupation authorities agreed for symphonic and chamber concerts to be organised under strict conditions and close supervision. They were held at the Conservatory of Music, before the building was destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising, as well as in cafes. Apart from the mainstream there was also an “underground” concert movement. Clandestine concerts were organised in private homes, among friends. Their programmes featured primarily Polish music banned by the occupying authorities. There was a lot of emphasis on premieres, which enabled the artists and the audience to hear new works, thus instilling in them a conviction that despite the horror around them Polish culture was still alive.

Grażyna Bacewicz’s participation in musical life during the occupation was limited to appearances at open and secret concerts.

- Concert programme of in Woytowicz’a Cafe (1944)

The young woman, who was caring for a large family, especially her ailing mother, gave birth to her only daughter Alina on 20 July 1942.

- Grażyna Bacewicz with her sister Wanda and daughter Alina in Ujazdowski Park (PWM)

- Grażyna Bacewicz with daughter Alina in the park, 1943 (PWM)

The fact that throughout this period she played at concerts, met other people, often offering them help, including shelter in her own flat, that she continued to compose – all this testifies to the strength of her character. Grażyna’s oeuvre from the occupation period is truly impressive given the conditions in which she had to work. Pieces she wrote at the time were: Sonata for violin solo (1941); Three Preludes for piano (1942); Piano Sonata No. 3, later withdrawn by the composer from the catalogue of her works (1942); Suite for two violins (1943);String Quartet No. 2 (1943) and Overture for orchestra (1943). The violin and piano Sonataswere premiered by the composer herself during clandestine concerts. Suitefor two violins was performed at one of such concerts by Irena Dubiska and Eugenia Umińska. The premiere of String Quartet No. 2took place on 21 May 1943 in Bolesław Woytowicz’s cafe “Art Salon” at ul. Nowy Świat 27. The performers were the Umińska Quartet: Eugenia Umińska — 1st violin, Tadeusz Ochlewski — 2nd violin, Henryk Trzonek — viola (he was later imprisoned by the Gestapo and shot on 3 December 1943 in a street execution) and Kazimierz Wiłkomirski — cello. The Overturewas performed shortly after the war, on 1 September 1945 in Kraków, during the Contemporary Polish Music Festival.

In her work the composer sought to remain faithful to the principle of the autonomy of art. She expressed her wartime experiences in words, in an unfinished manuscript ofPowieśc wojenna (Wartime Novel). However, the occupation was not just about the struggle to survive and organise concerts against all odds. It was also about maintaining family, friendly and social ties. Stefan Kisielewski recalled years later:

I spent many, many hours during the occupation at the Biernackis’ in ul. Koszykowa. It was such a welcoming and warm home; it provided such an excellent relief from the horror, sadness, despair and all other repulsive things brought to Warsaw by the Germans. And how much one ate and, especially drank there… oh my! Interestingly, although I was there often, I didn’t talk much with Grażyna about music, about composing. She didn’t like to express her musical feelings much; very delicate towards the others, she also jealously guarded the secrets of her work, her evolutions and transformations.

Stefan Kisielewski, ‘Grażyna Bacewicz i jej czasy’, Kraków, 1964, p. 12.

After the failure of the Warsaw Uprising Grażyna had to leave Warsaw with her family. When they were already under way, Grażyna remembered the suitcase with her compositions, her most precious treasure, which had been left at home. Yet in the face of the disaster around her, she decided not to go back to retrieve the manuscripts. Fortunately, a friend did go back and her manuscripts survived. Thus began the wandering life of the refugees. Its first stage was the Pruszków camp.

Grażyna was saved from being sent to Germany as a forced labourer by the fact that she had a two-year-old daughter (invaluable help in a more “just” selection of people was provided by the Central Welfare Council and Red Cross employees) and was caring for her elderly mother and wounded sister. What was also important was the profession of her husband, who was allowed to organise a ward of Warsaw’s Infant Jesus Hospital in Grodzisk Mazowiecki. In those extremely difficult conditions there was still a demand for art. Grażyna contributed to family’s modest budget by giving piano lessons.

The end of the war meant an end to unimaginable suffering for most people. For many living in Central and Eastern Europe it brought about a complete change in their life situation, often including having to settle in a new place. Poland was slowly rising from the ruins within new borders and in a new political situation. Initially, there were hopes for some agreement between the new government, and the former underground movement and the London government. Despite the uncertainty concerning the country’s future, an ethos of rebuilding was nevertheless emerging. The new administration seemed open to numerous initiatives in education and development of art. This was also conducive to new works being written. After a brief stay in Lublin, where she gave concerts with her brother Kiejstut, often in rooms without any heating, in the 1945/1946 school year Grażyna Bacewicz accepted an offer of the Łódź Conservatory and took charge of the teaching of violin and theoretical subjects. She continued to give concerts with Kiejstut, who years later, in a 1989 programme by Radio Łódź, recalled his collaboration with his sister in the following manner:

Our joint concert appearances, our radio recordings, album recordings took place in 1933–1955. In my work as a pianist my concert activities with my sister were a separate strand, it was – to put it briefly – creative in nature. It is quite obvious that this chapter in my artistic life is of special importance to me. There are various considerations at play here. The international stature of Grażyna’s performance of course determined the quality of our joint music making. That’s one thing. In addition, as Grażyna’s partner I could perform also her own compositions for violin and piano. This was a crucial moment in our collaboration. Direct, intimate – if I may say so – contact with Grażyna’s music, exploring her authentic, original vision of the works we performed together, getting to know the secrets of my sister’s musical thinking – these were fascinating, inspiring experiences for me. Experiences enriching my consciousness and musical imagination with new, original values.

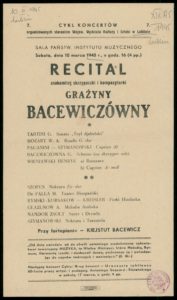

- Programme of Grażyna and Kiejstut Bacewicz’s concert in Lublin, 1945 (Polona)

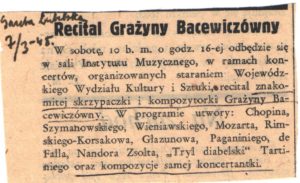

- Programme of Grażyna Bacewicz’s recital in Lublin, 1945 (Polona)

- Press note on Grażyna Bacewicz’s recital in Lublin (Gazeta Lubelska, 1945) (PWM)

The works Grażyna composed in 1945–1947 included Symphony No. 1, Violin Concerto No. 2, Symphonyfor string orchestra, Introduction andCapricciofor symphony orchestra, two Sonatas for violin and piano, String Quartet No. 3and two songs. She also wrote a number of educational and popular pieces, which was in line with the government’s cultural policy and initially did not go against the intentions of the artists.

In the first few years after the war artists did not yet have many problems with travelling abroad. In 1946 Grażyna went on a three-month tour of France, during which she performed Karol Szymanowski’s Violin Concerto No. 1at Paris’ Salle Pleyel with the Orchestre Lamoureux conducted by Paul Kletzki. She also took part in a concert entitled “Polish music under the occupation” organised by the Association of Young Polish Musicians in Paris and in the Franco-Slave Festival at the Sorbonne. On 23 May that year she and the pianist Jerzy Witas played herSonata da Cameraas well as pieces by other masters at Salle Gaveau. It was a charity concert organised by the Association of Polish Women. The proceeds went to Polish children who had suffered during the war.

- Press note on Bacewicz’s French tour (Gazeta Ludowa, 1946) (PWM)

In a letter of 13 May 1946, written to her brother Vytautas, who had been living in the United States since 1940, Grażyna wrote:

My concert at the Sorbonne was very successful, with encores etc. Now I’m preparing for my recital on the 23rd. I can’t play a lot at the hotel, but I have friends who have given me keys to their flats and I play at their places. I feel good in Paris and I’ve decided we won’t be living in the ruins. I will guide my family and their lives in a way that will gradually bring us here. I’m telling nothing to anybody, but I will have my way, if not soon, then in a few years. This won’t be easy, because I will have thousands of problems, but if I dig my heels in, if I want something badly, I will have it. Since Andrzej doesn’t want to live abroad, he will be the biggest problem. So far there have been two reviews of the symphonic [concert]. Very good opinions about me.

Making secret plans to settle in Paris, Bacewicz returned briefly to Warsaw, where she played Felix Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E minor at the Warsaw Philharmonic Hall. In 1947 she went to Paris again to perform with the pianist Jean Germain at “her” school — École Normale de Musique — presenting a programme featuring her own Sonata No. 2 for violin and piano as well as works by other composers. Positive reviews brought her satisfaction, but in her letters to Vytautas she writes about the difficult living conditions in post-war Paris. She did not complain about her situation; on the contrary, she writes about her successes and the friendliness of the French musical circles, but she asks him several times to send her violin strings and… cigarettes. She is worried by another thing as well. In a letter sent from Paris during her previous stay, on 17 June 1946, she writes:

The overall situation in France is lousy. People are hungry. I’m sorry that we will no longer be able to correspond with each other as openly as we have so far. When writing to Poland, do write with caution. They have arrested a musician, a great friend of mine, who is now in prison.

The atmosphere in Poland and the neighbouring countries was getting thicker and thicker, a fact that Grażyna meticulously recorded in letters to her brother sent from Paris. She knew that she could not have such freedom in describing the reality around her when writing from Warsaw. The situation was further complicated by a lack of news about her father. On 28 March 1946 the composer wrote to Vytautas:

We are very worried about Father, because people are sent in droves to Siberia from the Baltic countries. Our letters don’t reach him – nor is there any news from him. What will happen? Have you received any news?

Grażyna’s father, who considered himself to be a Lithuanian, left for Kaunas in 1923 and settled there. His family reconciled themselves to this situation. The letters exchanged between Grażyna and her brother Vytautas shed light not only on the relations within the family, but also on the composer’s personality [see Personality].

During her stay in Paris in 1947 Grażyna was able not only to cultivate her artistic contacts but also to shop in stores offering goods that were hard to come by in Poland. The French capital was quickly recovering. In a letter to her brother of 16 April 1947 Grażyna writes:

I saw Kletzki – an excellent conductor. In June I’ll sent him my scores – as agreed – to Switzerland where he lives. Today I went shopping to buy presents for the last time. I bought shoes for Andrzej, because they’re v. expensive back home, a coat for Alinka and some other things. If I manage to bring all this into the country, it’ll be a miracle! For our mum I have a silk shawl, a blouse, stockings, a shopping bag, a brooch and perfumes. But don’t say anything in your letters.

In May 1947 Grażyna heard about a planned performance, during a concert organised at the Paris Radio, of her Overture, Quartet No. 2and Suite for two violins. It seemed that France was a place where she could carry out all her plans and where she would be happy. However, she was unable to implement these plans. Was it caused by the political situation, the various restrictions tightening around Poland? Or was it the still high standing of artists, especially those who had already gained recognition and for whom the new authorities were able to look after, for example by granting them scholarships or awards? In a letter from 14 May 1947 the composer informed her brother:

I’ve just been given Images Musicales featuring my photo. The next issue will apparently have a brilliant review. A letter from Wanda has come, announcing that the ministry has granted me 40,000 zlotys, so we now have money for our holidays. I didn’t apply for it. I’ve also received a letter from Kiejstut, who says that I’m to play Tchaikovsky in Łódź. What a nuisance, I wanted to get some rest, but oh, well. So I’m leaving tomorrow. I’ll be in Warsaw on the 17th.